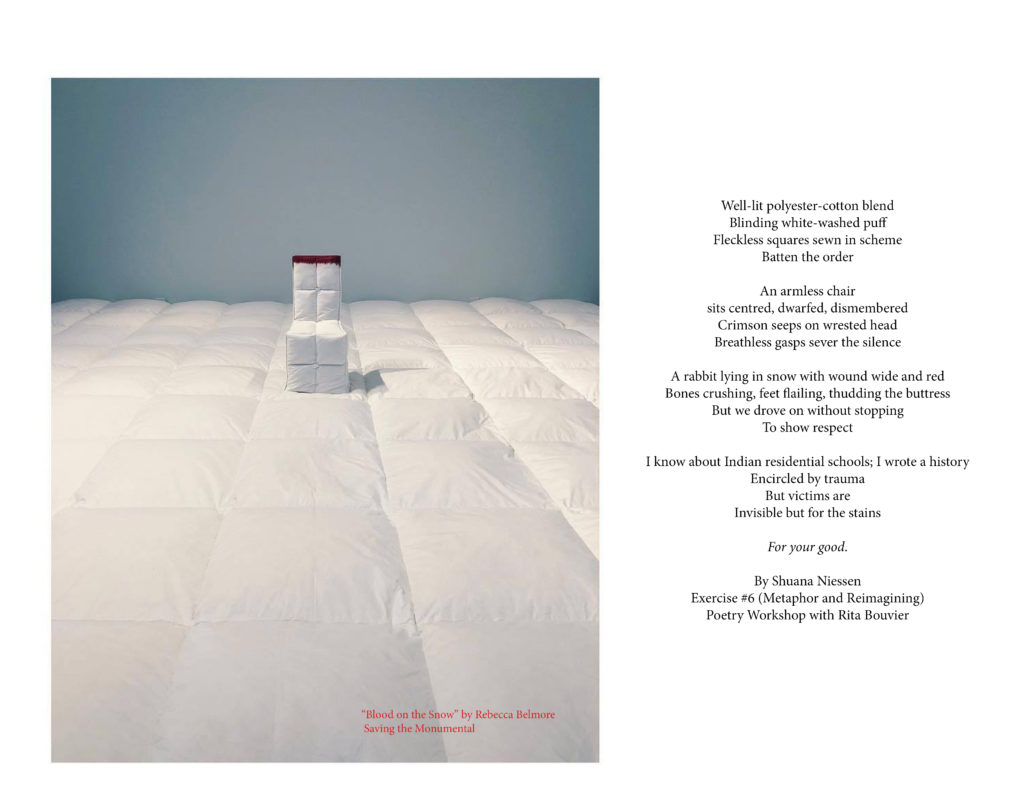

Commissioned Author: Shuana Niessen

Published in 2017 by the Faculty of Education.

English and French versions

Download a free copy at https://www2.uregina.ca/education/saskindianresidentialschools/

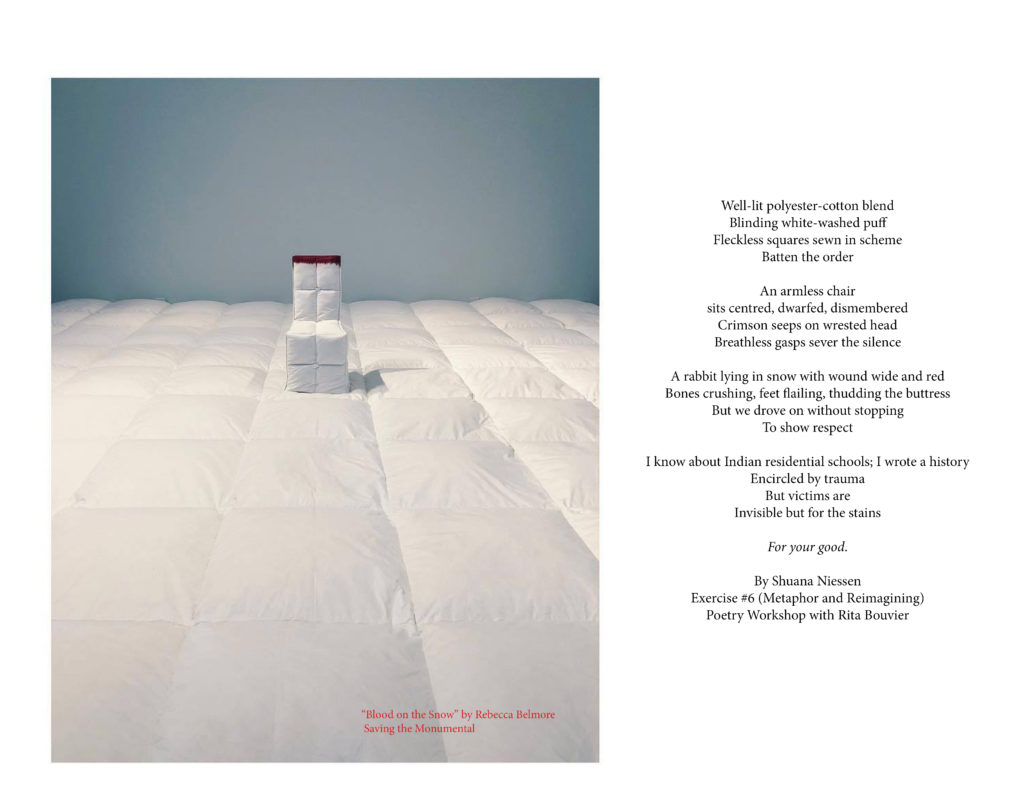

Commissioned Author: Shuana Niessen

Published in 2017 by the Faculty of Education.

English and French versions

Download a free copy at https://www2.uregina.ca/education/saskindianresidentialschools/

It is surprising really that I grew up here and it wasn't until my fifties that I became aware of treaty. Certainly, I'd heard the term before, mostly to do with tax exemption and status, but I didn't realize that treaty was about living and walking in a good way with one another.

Privilege: a right or immunity granted as a peculiar benefit, advantage, or favor.

~Merriam-Webster dictionary

Lately there’s been a lot of talk about being White and the unearned privileges associated with this social racial classification. In looking at the often-taken-for-granted privileges of being White in North America, I asked the question: “Why do we talk about privilege in terms of economy, as if there is a shortage on privilege?” I think this might be an odd question, since by definition the concept of privilege involves those who “have” and those who “have not.” But why do we (humans) grant privileges to some and not others? And, why do we make arbitrary social standards about who will be granted privilege and who not? Can’t we give the rights and advantages of privilege to all–rich and poor, majority and minority, white and coloured? Why does our society, and societies all over the globe have a system of privileging some over others?

Peggy McIntosh talks about privilege in her article, White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.

She creates a list of unearned privileges which accompany being part of a dominant group:

1. I can if I wish arrange to be in the company of people of my race most of the time.

2. I can avoid spending time with people whom I was trained to mistrust and who have learned to mistrust my kind or me.

3. If I should need to move, I can be pretty sure of renting or purchasing housing in an area which I can afford and in which I would want to live.

4. I can be pretty sure that my neighbors in such a location will be neutral or pleasant to me.

5. I can go shopping alone most of the time, pretty well assured that I will not be followed or harassed.

6. I can turn on the television or open to the front page of the paper and see people of my race widely represented.

7. When I am told about our national heritage or about “civilization,” I am shown that people of my color made it what it is.

8. I can be sure that my children will be given curricular materials that testify to the existence of their race.

9. If I want to, I can be pretty sure of finding a publisher for this piece on white privilege.

10. I can be pretty sure of having my voice heard in a group in which I am the only member of my race.

11. I can be casual about whether or not to listen to another person’s voice in a group in which s/he is the only member of his/her race.

12. I can go into a music shop and count on finding the music of my race represented, into a supermarket and find the staple foods which fit with my cultural traditions, into a hairdresser’s shop and find someone who can cut my hair.

13. Whether I use checks, credit cards or cash, I can count on my skin color not to work against the appearance of financial reliability.

14. I can arrange to protect my children most of the time from people who might not like them.

15. I do not have to educate my children to be aware of systemic racism for their own daily physical protection.

16. I can be pretty sure that my children’s teachers and employers will tolerate them if they fit school and workplace norms; my chief worries about them do not concern others’ attitudes toward their race.

17. I can talk with my mouth full and not have people put this down to my color.

18. I can swear, or dress in second hand clothes, or not answer letters, without having people attribute these choices to the bad morals, the poverty or the illiteracy of my race.

19. I can speak in public to a powerful male group without putting my race on trial.

20. I can do well in a challenging situation without being called a credit to my race.

21. I am never asked to speak for all the people of my racial group.

22. I can remain oblivious of the language and customs of persons of color who constitute the world’s majority without feeling in my culture any penalty for such oblivion.

23. I can criticize our government and talk about how much I fear its policies and behavior without being seen as a cultural outsider.

24. I can be pretty sure that if I ask to talk to the “person in charge”, I will be facing a person of my race.

25. If a traffic cop pulls me over or if the IRS audits my tax return, I can be sure I haven’t been singled out because of my race.

26. I can easily buy posters, post-cards, picture books, greeting cards, dolls, toys and children’s magazines featuring people of my race.

27. I can go home from most meetings of organizations I belong to feeling somewhat tied in, rather than isolated, out-of-place, outnumbered, unheard, held at a distance or feared.

28. I can be pretty sure that an argument with a colleague of another race is more likely to jeopardize her/his chances for advancement than to jeopardize mine.

29. I can be pretty sure that if I argue for the promotion of a person of another race, or a program centering on race, this is not likely to cost me heavily within my present setting, even if my colleagues disagree with me.

30. If I declare there is a racial issue at hand, or there isn’t a racial issue at hand, my race will lend me more credibility for either position than a person of color will have.

31. I can choose to ignore developments in minority writing and minority activist programs, or disparage them, or learn from them, but in any case, I can find ways to be more or less protected from negative consequences of any of these choices.

32. My culture gives me little fear about ignoring the perspectives and powers of people of other races.

33. I am not made acutely aware that my shape, bearing or body odor will be taken as a reflection on my race.

34. I can worry about racism without being seen as self-interested or self-seeking.

35. I can take a job with an affirmative action employer without having my co-workers on the job suspect that I got it because of my race.

36. If my day, week or year is going badly, I need not ask of each negative episode or situation whether it had racial overtones.

37. I can be pretty sure of finding people who would be willing to talk with me and advise me about my next steps, professionally.

38. I can think over many options, social, political, imaginative or professional, without asking whether a person of my race would be accepted or allowed to do what I want to do.

39. I can be late to a meeting without having the lateness reflect on my race.

40. I can choose public accommodation without fearing that people of my race cannot get in or will be mistreated in the places I have chosen.

41. I can be sure that if I need legal or medical help, my race will not work against me.

42. I can arrange my activities so that I will never have to experience feelings of rejection owing to my race.

43. If I have low credibility as a leader I can be sure that my race is not the problem.

44. I can easily find academic courses and institutions which give attention only to people of my race.

45. I can expect figurative language and imagery in all of the arts to testify to experiences of my race.

46. I can chose blemish cover or bandages in “flesh” color and have them more or less match my skin.

47. I can travel alone or with my spouse without expecting embarrassment or hostility in those who deal with us.

48. I have no difficulty finding neighborhoods where people approve of our household.

49. My children are given texts and classes which implicitly support our kind of family unit and do not turn them against my choice of domestic partnership.50. I will feel welcomed and “normal” in the usual walks of public life, institutional and social.

Many of these privileges have to do with power, and access to resources such as jobs, decision-making authority, food, money, and status. Why don’t we tend to want to share and extend power to all people in a society? Why don’t we allow open access to resources?

In a sense, I think it comes down to the value of taking care of your own. I think of a scene in Linda Crew’s Children of the River, in which a Cambodian mom, fleeing from Cambodia for her life along with many others, sits on board a ship, nursing her infant, and refusing to share her milk with another infant whose mother is sick; her milk has dried up. The infant, whose mother is sick, dies. The other lives. Why this privileging of one infant over another? Their race and class are the same. But one belongs to the mother, and the other does not. Had the mother agreed to feed the other infant, would both infants have died, since she did not have enough water to keep up her own supply of milk? Resources are limited and allowing open access to resources would mean that everyone would have less. But why use race as a marker for privileging some and not others? I guess the answer lies in who has access to the resources, and those who have access, wanting to take care of their own. I’m not saying this is right, or good. I’m just exploring the question: “Why do we talk about privilege in terms of economy?”

Written September 28, 2006

————————————— Added November 2016 (10 years later)

Economy: careful management of available resources

I now think the problem lies in how White European settlers view the land as something to be owned. Our’s–this land, these resources belong to us, and with this thought, we can justify taking land, resources, from others whom we deem unworthy–those who are not ours, who differ from us in some way we deem important.

Those who have access to the resources wanting to take care of their own, in turn owning the resources. Many Indigenous groups rightfully criticize White European settlers for their concept of ownership of land. For them, the land and all resources in the world are not owned by anyone. The earth (the land, its resources) is to be respected for its ability to care for us–as a mother who cares for her children. In this sense, the world owns us, cares for us, and we all belong to the earth. In this worldview, there would be no way of privileging one over another due to ownership. And from a Christian worldview, the earth, which cares for us as a mother cares for her children, is a gift from the Creator. (It is easy to see how we have been misled by our worldview and thinking the earth itself is ours.) Our care is a gift…and Christians are called to be good stewards of her care–to, also, treat the earth with respect and consideration. If there is to be an economy under this concept of earth, then what is required is careful management of the earth’s resources, ensuring that all of the earth’s children of every race, ethnicity, religion, language, sex, gender, age, and so on, have access to what they need to survive–to the earth’s care.

Okay, so I’ve been thinking about citizenship and how this concept relates to rights and responsibilities in the lives of school-aged children. I am considering the question of who has the greatest right and responsibility to decide what is in the best interest of children when it comes to the issue of school attendance and curriculum: parents, state, or the children themselves? I recently attended a seminar in which the presenter described, among other scenarios, the problem of parents who won’t allow their children to attend school past a certain age. He was considering the impact that this restriction has on their children, and what the state can do to ensure the rights of children are attended to despite parental religious beliefs and the culture in which children are raised. It seemed to me that his basic premise was that children, especially teen-aged children, ought to have limited autonomy from their parents, and the freedom to choose an education if they wish. However, he considered the problem that children such as these, might be strongly influenced to please their parents, or fit into their community, and in such cases, may not be able to choose in their own best interests, and in such cases, ought the state act to intervene on behalf of the children–in their best interest?

My first response to this is that it is kind of appalling to think that the state could override parents’ and children’s’ wishes. Is the state truly able to objectively act in the best interest of children? Lawyers caution parents who are separating to resolve their differences regarding the shared responsibility for their children, because if it goes to court, the judge will then make the decision as to what is in the best interest of the children. Further, the judgment or ruling is rarely in the best interest of the children. It is understood that parents are best situated to make those decisions.

As I consider how much power parents or states or individuals ought to exercise in these kinds of decisions, I picture concentric circles moving outwards, getting larger from the individual to family to community to province to nation to continent and so on. And each of these circles represent a type of citizenship, which includes rights and responsibilities. I’m first of all an individual, then I am an individual within a family unit, and then I am part of a family within a community, whether it is religious or some other organization, and so on. But at what age can we consider a child capable of expressing full citizenship at any level? And until the child is capable of full citizenship, who is to act on their behalf? This has always been the parents responsibility, and their responsibility gives them certain rights.

I overheard a teacher griping that parents don’t seem to understand that their kids also belong to the state. I joined the conversation saying, “Of course they don’t. Where was the state at 2:00 a.m. and 4:00 a.m. feedings? and the colic? and nursing the child through illnesses, and potty training, and terrible two temper tantrums, and all that parents do for their children? Of course they are going to resent the state telling them, at the age of five, ‘Thanks, you’ve done a great job, now take a back seat and we’ll take it from here!’” I think if the state wants to have a few more rights, then they ought to show a bit more responsibility. Like in France, the state is involved in the process of raising the children, offering support to care givers through the free nanny, cooking, and housecleaning services. Now, there’s some help that would create a bit more willingness to let the state be more involved in deciding what is best for my kids! More rights mean more responsibilities.

If either the parents or the state removes themselves from responsibility to the other, there is a breach in their relational contract. Parents ought not to exclude the state’s interests in their role in raising children, and the state ought not to exclude the parents’ interests in their role of educating the children. Ultimately, I do believe in some autonomy for the children themselves. The impact of overriding parents and the child, with the state imposing its values on the closest environment of the child–the inner circles of self, family, and religious community–would seem to have more damaging psychological implications, than the child being removed from school with the parents in agreement or both the parents and the child in agreement about the decision.

Written February 9, 2009

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

two roads diverged in a wood, and I —

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

The metaphor of the river gives the feeling that our journey is less about our choosing, and more about the currents that drive us. Is life a river or a road? I guess it is both. If you have been raised in the West as part of dominant society,the privileges you take for granted will effect a belief that life is a series of choices, a simple matter of choosing your direction when you come to a fork in the road.What is it that we can’t control? The weather sometimes shakes our illusions of power. There are those born into poverty or who are physically or mentally challenged in some way, who realize that the metaphor of the road only works for a few privileged people in the world.

The river, with its currents, sharp rocks, rapids and waterfalls more accurately depicts life for most of the world. Famine, hunger, disease, poverty, disability, war, crime, and exploitation are the daily realities of most of the world’s population. These are the realities through which people must navigate, all the while seeking to become whole, to meet their responsibilities, to take care of those they love.

I realized when taking my Ed Psych course that the “locus of control” theory, seems a very Western theory. Too, our aversion to passive sentences in the English Languages expresses an insistence that we are the subjects of our own sentences, not the objects. Perhaps we in the West like to delude ourselves with the idea that we choose our paths. There are so many invisible forces that drive our choices, like the competitive nature of capitalism, the pressures to achieve academically, the psychological wounds of growing up…

Lately the issue of public versus private has been on my mind. Many bloggers are describing their feelings of unease over the mixing of the public and the private through the blogging medium. I certainly feel this tension. I have a couple of blogs that I keep up: a personal blog that relays information to family and close friends, and this public one that I use to document general information about my life and thoughts.

I have long thought that blurring private with public is a mistake. The feminist movement had difficulty with these boundaries because the notion of “feminine” was associated with the private life, and “masculine” was associated with public life. Many women thought that in order to bring themselves to the public life, they had to mix private with public. They didn’t consider their capability to take on a masculine, public role. (Nor was it socially acceptable for them to do so.)

Honor of the Queen by David Weber is a sci-fi novel that explores this theme of feminine and masculine roles in society. Honor is a woman, and the captain of the starship, Fearless. She is tall, strong, brave, smart and objective—everything one can hope for in a good captain. In fact, if I replaced “she” with “he” in the story, there are only a few moments where I would feel that the “he” doesn’t fit. At one point, after work in her private quarters, the story briefly describes Honor’s personal enjoyment of hot chocolate and cats. Another point is when Honor empathizes with one of her officers and he becomes embarassed. Here the reader realizes that Honor, to be successful, must keep feminine characteristics at bay. Honor’s mother is another character that highlights how Honor is unusual, and therefore successful. Honor’s mother teases her about men, and love, but Honor is embarrassed by her mother’s comments and gives them very little time, thinking only how unattractive she would be to the opposite sex, due to her size and strength, and position.

I think this story is really talking about public and private roles in society, as well as masculinity and femininity. Codes of masculinity are rules of public, war-like, competitive behaviour, and codes of femininity are codes of private, peace-loving, domestic behaviour. When alone Honor is free to think in terms of love and relationships, comforts, beauty, and emotion. When in her professional role, Honor must be objective, strategic, strong, and brave. Still, Honor is confused about her public and private roles, and does not develop a strong personal life. (This may reflect the author’s own confusion about roles and code-switching in different contexts.)

Throughout time the blurring of public and private has caused problems. Men, who were raised to be knights, warriors, protectors, and hunters, found domestic life difficult because it felt like they were being feminized at home. Some responded to this by leaving, or engaging in risk-taking activities whenever possible to prove they were still men (think of Deliverance) and some responded by acting like aggressive warriors in their own home, abusing and battering their family members when the security of the family seemed threatened. (There are of course many responses but these are generalizations) Women, bringing their private, domestic code into the public life made things very complicated, and they were responsible for creating destabilizing effects in the workplace. Even now there is a real conflict between top levels of government, who must be responsible for protecting the business, organization, or nation, by competitive behavior, or engaging in war (masculine/public roles) and those who are against any type of aggression, muscle-showing, or competitive roles in society.

My opinion is that there is a time and a place for everything. Code-switching is an important skill in all areas of life. We don’t go into a high-class restaurant and act like we would at McDonalds. We code-switch. We try not to use jargon when we go for a job interview. We code-switch. I think, too, that in public life, we need to code-switch. I don’t think that domesticating the public world is any more beneficial to the public, than publicizing the private is to the private life. I also find I’m very uncomfortable in a world that blindly accepts Foucault’s idea that anything private or hidden is shameful and must be brought out into the public eye. There is nothing shameful about the private life remaining private. But that is another topic…